When an author becomes really famous they earn the right for first editions of their subsequent books to be more opulent than their earlier efforts. and Elizabeth Gilbert’s The Signature of All Things (TSOAT) is gorgeous. Since the book is set in the 18th and 19th centuries, the look of it is antique, with unevenly cut, thick ivory pages and a dust jacket printed to look like aged parchment. There are dreamy colored illustrations of orchids on the end papers and the hardbound cover is a soothing green-tinged ivory with an olive colored spine, the author’s initials stamped in gold on the front. The feathery edges of the pages are soft and the book is very sensual, befitting some of the subject matter. My copy is even signed!

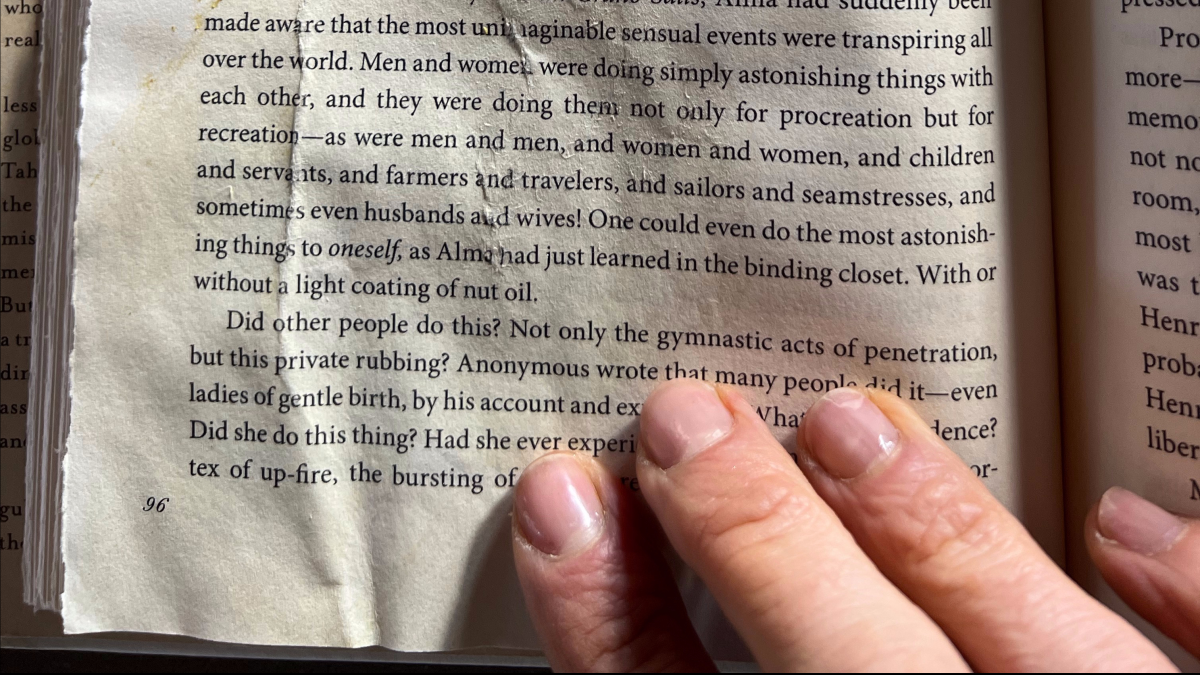

Every time I picked TSOAT up, I was filled with admiration for the book as an object, but that didn’t stop me eating a bowl of cauliflower soup while reading it. I spilled hot soup almost the exact color of the book’s cover all over page 96, which happens to be the page that main character Alma Whittaker discovers pornography–and thus, the delights of masturbation–in an old trunk of books to be sorted for her family’s vast library. The soup soaked through three or four pages and I had to stop reading and prop it up to dry for several hours. As the perfectionist owner of a selfish little library, the soup stain that marred several pages of the beautiful book meant only one thing–I was sure to order a new copy and sadly relegate this “ruined” one to the donation bin.

I couldn’t help but wonder: I’d read the book at least twice before and remembered all the masturbation and gently pornographic bits quite vividly, so it wasn’t shock that caused me to spill my soup, I just happened to hit the bowl with my knee whereby at least a quarter cup of soup leapt onto the page. But like they say, there are no accidents, and the thickened, wrinkled page, stained with what on a hotel mattress would look like dried semen, is like a shameful bookmark.

The book begins with the youth of Alma’s father, Henry, a cunning, hardworking rascal who avoids hanging for theft by becoming an invaluable member of several sailing expeditions around the world sent out to gather botanical specimens. He moves from England to Pennsylvania with his intelligent, practical, hard working Dutch wife and they become incredibly wealthy. Their only child, Alma, is taught to speak several languages, is introduced to the leading botanists and thinkers of her day and becomes an accomplished, extremely dedicated botanist herself. The first half of the story never lags and I looked forward to reading it every chance I got.

This is a novel that inspires me to pursue knowledge. As I was reading, I stopped to contact a Spanish teacher and sign up for her class. I thought about the extraordinary pink and green granite table I have on my property and looked up types of granite and learned that it may have come from Finland, that granite is compressed magma (liquid minerals) and is igneous rock, not conglomerate or sedimentary as I had thought, and that the mossy green color was probably epidote and the pink is feldspar and quartz. Until I looked all this up I had thought that all igneous rock was black or grey. But I’m sure that’s oversimplified–metamorphic rock might be more correct. There’s so much to know!

I won’t go into more of the plot except to say that parts of the section in which Alma spends time in Tahiti does lag a little, and I found myself wanting to skip ahead. Also, I bet Elizabeth Gilbert traveled to England, Pennsylvania, Amsterdam and Tahiti for research, and thinking about that and trying not to be jealous distracted me. In addition to a beautifully printed book, travel is an envied perk of the super successful writer.

One of my favorite quotes in the book is from Montaigne, a French philosopher who lived in the mid-1500s, died at age 59 (my exact age) and interspersed personal anecdotes in his philosophical essays, saying, “I myself am the matter of my book.” Critics thought this self-indulgent but I relate! Anyway, Montaigne said, “There are two things I have always found to be in singular accord: super celestial thoughts and subterranean conduct.” Television evangelists are the obvious examples of how easy this truth is to observe and I usually find out that people who are vocally critical of my flaws and behavior are hiding their own much darker and more dramatic character defects. Alma recalls the incredibly apt quote when she discovers that the husband she thought chaste, almost angelic; the man who made her feel ashamed of her natural sexual urges, is a closeted homosexual.

Another thought-provoking quote for me was about evolution. “The greater the crisis the swifter the evolution.” This made me think more about evolution of the spirit than of plants and animals. A personal example is when I stopped drinking. The drinking crisis had come to a point that I needed to completely change my life. Slowly, then all of a sudden, I evolved into a sober creature, a significantly different person. Another personal example was when Donald Trump was elected president and shortly after we had our first horrific wildfires. I joined Rotary to try to get into “the solution,” and become more involved in the community. Yet another spiritual evolution occurred after my marital separation–I was so shocked by my husband’s behavior and my new situation that I couldn’t sleep, didn’t eat (much) and began doing activities that I hadn’t done before, such as 5am meditation, kundalini and constant gardening. I let go of criticism and kept a wide open heart. I wish that somewhat manic adrenaline wave could have gone on and on. Is there such a thing as backsliding in evolutional theory??

Gilbert’s language is fresh, humorous, delightful. Some of the original descriptions are so wonderful that it seems a shame they are buried in a novel and not highlighted in a poem. I love the description of the trans-American railway as steel stitches sewing the post-Civil War country firmly together.

There’s so much to love about this book, then again, I’m the ideal audience for the subject matter–an avid reader, a lover of language, nature and libraries, the resentful sister to a much more beautiful female specimen (another of the book’s topics), a champion of masturbation and and the recipient of criticism by those who claim the moral high ground and who I later find have feet of shit-covered clay. I was surprised to find that the book only received 4 stars from Goodreads. I was able to find another “very good” copy for under $6. We shall see if it is a first edition of the same quality as the now soup-stained one that I currently own. It is extremely unlikely that it will be signed. Sigh.

The pantheism of the book also spoke to me. There is plenty to be in awe of in our universe, seen and unseen, that I don’t feel the need to invent or try to figure out a higher power and can’t stand people trying to tell me I need to subscribe to this or that dogma. As Alma says, “I have never felt the need to invent a world beyond this world, for this world has always seemed large and beautiful enough for me.”